The power and duty of the King to dismiss the present prime minister is incontrovertible within the Constitution and the established law of Malaysia, whatever Mahiaddin’s dwindling circle has to say.

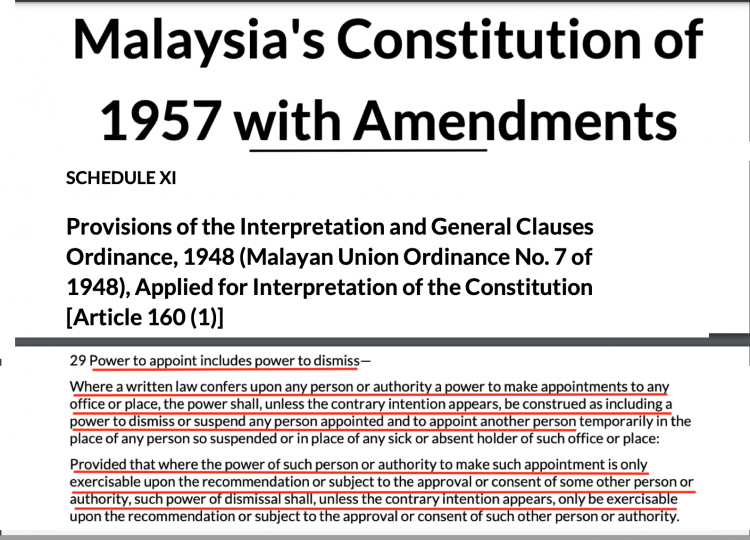

It lies in the convention established by the General Clauses Act (UK) of 1897 which was incorporated in the Malaysian Constitution under Schedule 11 Section 29.

The provision (set out almost on the penultimate page of Constitution) lays down an obvious principle that the power to appoint includes the power to dismiss as is made available and explained by the Commonwealth Legal Information Unit and elsewhere:

“29. Power to appoint includes power to dismiss – Where a written law confers upon any person or authority a power to make appointments to any office or place, the power shall, unless the contrary intention appears, be construed as including a power to dismiss or suspend any person appointed and to appoint another person temporarily in the place of any person so suspended or in place of any sick or absent holder of such office or place” [Malaysian Constitution 1957, Schedule 11 Section 29]

As most Malaysians have become aware given the constitutional battles over the past few days the Constitution clearly gives the power to the King to appoint as his prime minister the individual that he has reason to believe commands the majority support of the elected representatives of Parliament.

That majority must then be tested in the house: if requested by means of a No Confidence Motion put forward by the leader of the opposition. If the appointee fails to or ceases to enjoy the confidence of the House then he should tender his resignation naturally.

If the shameless fellow refuses to tender his resignation, as appears to be the present case, then the King is therefore entirely within his remit according to the law of Malaysia to invoke his authority to dismiss given there is no “contrary intention” expressed in the provisions for the appointment which would undermine that principle.

The second paragraph of the very schedule also reenforces the principle that the approval and consent of the majority of MPs is also subsequently required:

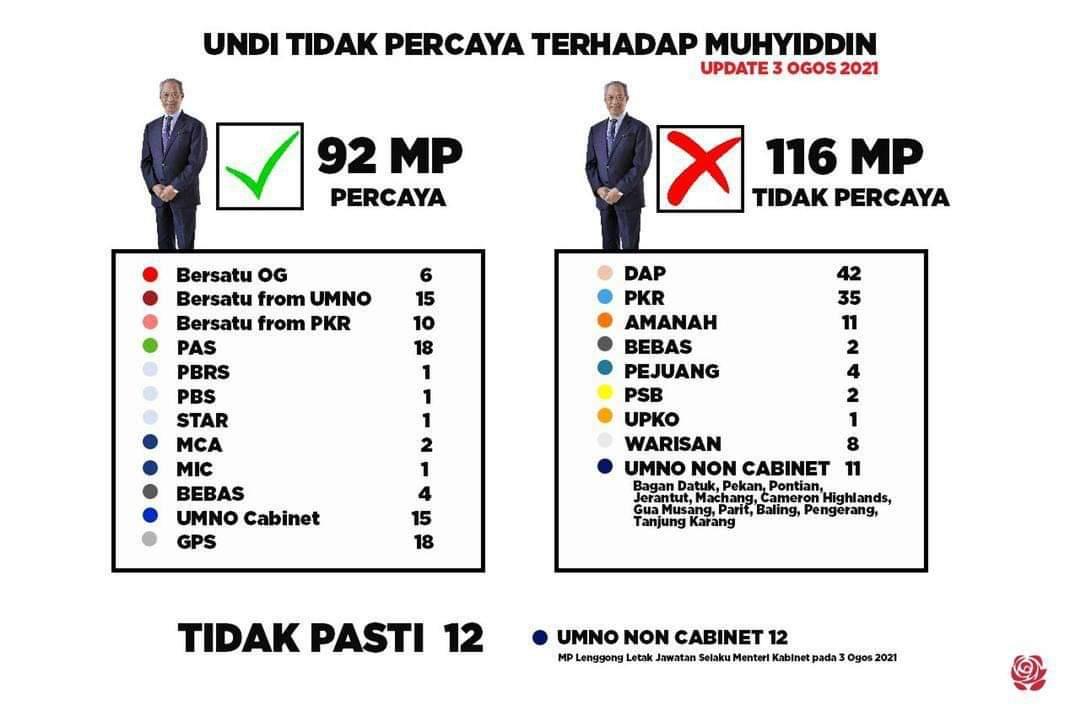

The tipping point on this matter was reached on Tuesday when 11 members of UMNO publicly stated their withdrawal of support from PN and revealed that they had further communicated their position in writing to the King himself. This has left the King and the entire country in no doubt that the majority of MPs want to see the back of Moo.

In the same way that the King had the power to appoint Mahiaddin, subject to the satisfaction of MPs therefore, he now has the power to dismiss given the dissatisfaction of those MPs.

At which point he once again has the power to either appoint an alternative leader whom he believes can command a majority or to dissolve Parliament entirely, which is also within his power.

Given the situation of the pandemic this latter option is universally considered unacceptable in the immediate term. If Mahiaddin is not prepared to do the honourable thing and resign, it is entirely within the authority of the King, and indeed it is incumbent on him, to call to the Palace the most likely person to command a majority to lead.

There is no future for Mahiaddin Yassin as prime minister.