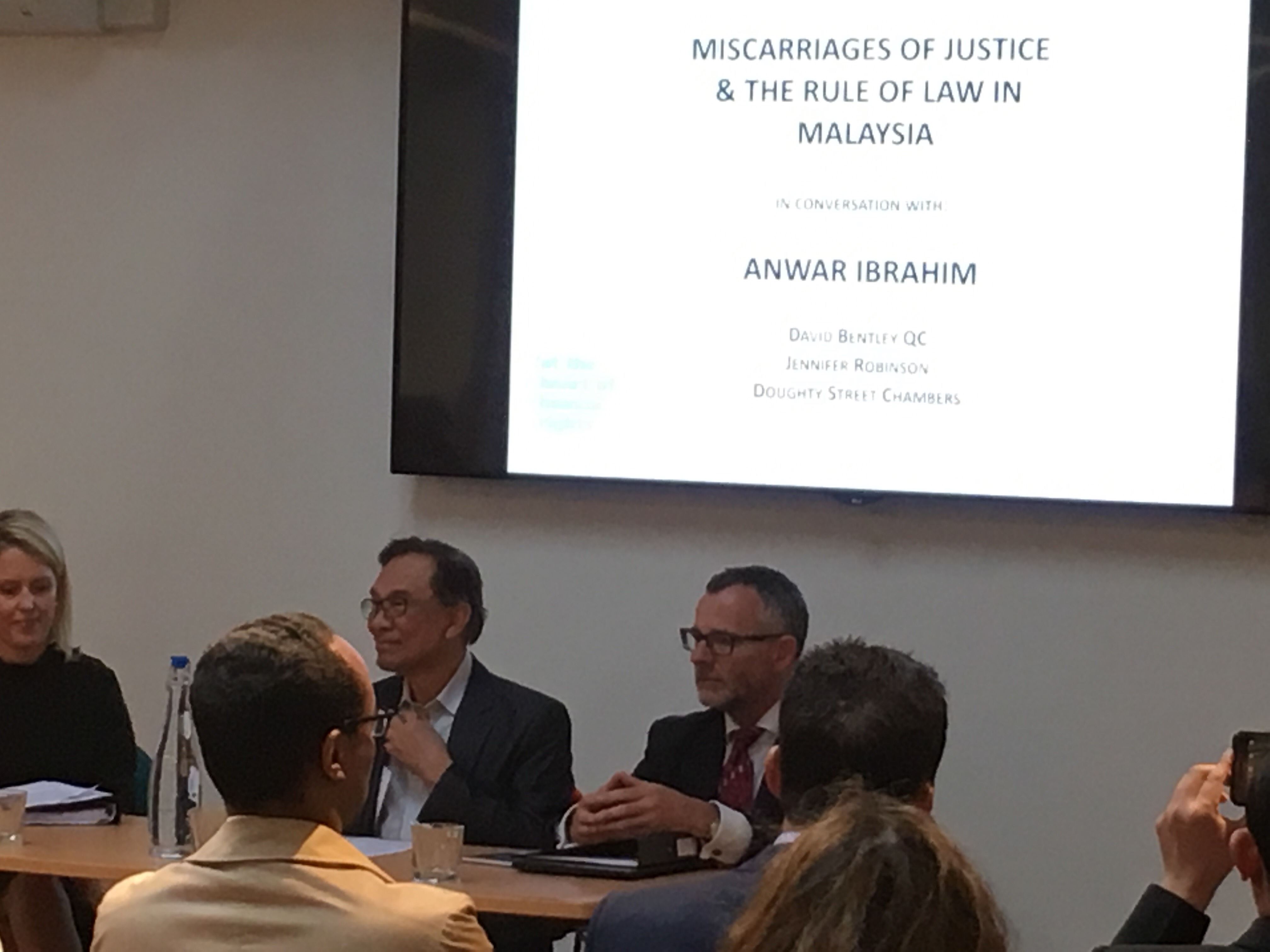

Invited to speak at London’s Doughty Street Chambers, famous for its human rights focus, Anwar Ibrahim today stunned his audience by revealing that he has requested the firm to continue with the case they had drawn in his defence – even though he has now been fully pardoned and exonerated by the King.

“I want to have [my case] set out and reviewed in court and to have it judged purely on the principles of law – this would show the beginning of the rule of justice in Malaysia”, he explained.

Opening the discussion on ‘The Future of the Rule of Law In Malaysia’, David Bentley QC told the audience how their chambers had been approached last year to attempt one last review of Anwar’s case, in order to see if there remained any legal channels in Malaysia to overturn the verdict.

He explained that the situation had presented itself as bleak, not least because Malaysia lacks provisions for oversight review by the Federal/supreme court to make sure justice has been served. He said this meant that the Federal Court could not be requested to re-open the case.

David Bentley said that his team had also been troubled by the fact that, unlike for example in the UK, an acquittal in a criminal case could be challenged by the prosecution, as had taken place in Anwar’s situation.

Anwar had been found not guilty by a High Court judge, Bentley pointed out, on the grounds that the crucial DNA evidence used against him had been shown to be suspect and inadequate by two eminent Australian scientific experts. In normal circumstances this ought to have been the end of any criminal prosecution and indeed the Malaysian High Court judge had deemed it so.

However, when the case was unsually sent upwards to first the Appeal Court and then Federal Court, the London lawyers said they were dismayed to discover that the evidence of the respected scientists had been ridiculed and dismissed by the higher judges. In one ruling the DNA experts were described as “armchair observers”, said Bentley, for reasons that were not clarified.

For this reason the team from Doughty Chambers had constructed a last ditch challenge condemning the ill-informed scientific basis of the later rulings (where the judges had not themselves heard the expert evidcence). Even so, they acknowledged that to obtain an order to re-open matters would be a cutting edge achievement in terms of Malaysian law.

The Doughty Chambers team produced their papers at the start of the year, but then found themselves over-taken by events on May 9th – for which they were delighted.

Anwar then spoke about his situation, pointing out that many others have suffered under archaic legal processes in Malaysia, which he as a politician has had a unique advantage of viewing first hand (by virtue of joining them in prison).

He made clear that he has become a passionate advocate for prison and penal reform as a result, which brought several rounds of claps.

He spoke passionately about his relief at the words of the Agong, who had assured him that the pardon had been granted not because he had the power to do so, but because of his personal and sincere belief that Anwar’s case was a travesty, so he wanted to reverse a miscarriage of justice.

It was for this reason that he was granted not merely a pardon, but a total exoneration from all charges.

Yet, in the cause of modernisation and judicial reform, Anwar then went on to explain that he was minded to encourage his London lawyers to continue to press their case through the Malaysian courts, in order to test those reforms. Pakatan Harapan had been won the election on a reform agenda, he said, “who is prime minister doesn’t matter, we are commited”

He explained that to find justice through a reformed Malaysian system would be a test of his mission, but did not elaborate on whether such a move could be contemplated in his own case at this stage of the planned transformation to a legal system free from interference.