Is the 1MDB scandal essentially a rip-roaring yarn about a brilliant young lad from Penang, who bamboozled a corruptible prime minister, fooled the world’s banks and managed to pull of a series of record billion dollar heists?

This may be the narrative that powerful figures in the finance world would like to be established, especially with the regulators in the United States, so miscreants can pay a few fines and move on. However, that would be unacceptable.

For a start, Malaysia is owed the best part of US$600 million from one of the world’s biggest banks, Goldman Sachs, for services that ought to have cost a fraction of the amount and which facilitated the theft of billions from the fund.

Those high charges and the failure by the bank to apparently spot the criminal intent behind the hasty and secretive borrowing of public money by the Malaysian PM and his advisor, Jho Low, raise questions about a whole network of other transactions between various banks and Malaysian entities like 1MDB.

Since none of those financial entities are staffed by fools, the conclusion must be that systematic failures by key decision makers were the product institutionalised criminality at least in some of these cases (Switzerland has stated that it is investigating Falcon Bank as a criminal entity) the full extent of which deserves to be fully investigated and punished.

Malaysia should be restituted and the wider problem examined. These banks all made serious cash processing 1MDB’s public money and it is an unspoken reality that, thanks to the weaknesses of regulation and the easy nature of off-shore finance, this abuse has become systemic all over the globe.

1MDB has lifted the lid on this long concealed scandal and it is now for regulators to dig deep into the sort of obscure transactions and offshore instruments being utilised for example by Goldman Sachs on behalf of 1MDB, in order to determine to what extent they represent criminal activity on the part of the bank or just some individuals.

‘Dr’ Tim Leissner, the man in charge of Goldman Sachs in South East Asia at the time of the massive 1MDB bond deals totalling US$6.5 billion, has already been arrested in the United States and is cooperating fully with with the authorities working the case.

Sarawak Report has learnt that the matter is now under the purview of the Department of Justice’s ‘Foreign Corrupt Practices Act Enforcement Unit’, part of the Securities and Exchange Commission in Washington DC. Chief of the unit is the prosecution lawyer Daniel Khan, a specialist in international fraud and money laundering cases, who has now taken personal charge of examining the multi-billion dollar scandal.

If Goldman Sachs are properly investigated over the matter, it could for the first time shine the full glare of publicity on exactly how top banks have serviced kleptocrats to the detriment of billions of people across the globe. Thanks to the outrageous use of the off-shore system it has become impossible for ordinary citizens or journalists to make any inroads into how public money is being handled in such cases – so only law enforcers can expose a problem which appears to be spiralling out of control.

Goldman And The Use Of Off-shore To Raise Public Money

The first question for Goldman Sachs is surely what could possibly justify a major bank agreeing to engage in obscure and pricey off-shore instruments to raise dollars for government-owned bodies in Malaysia, instead of functioning on the open market?

More has started to emerge over just the past few days on this front. Sydney finance writer Ganesh Sahathevan has pointed to a fascinating detail from a recent statement to the London Stock Exchange by the Abu Dhabi sovereign fund IPIC relating to the controversial 1MDB Energy (Langat) ‘power purchase’ loans:

IPIC made an announcement to the London Stock Exchange on 10 October 2018. The announcement concerned, among other things, the resumption of its 1MDB guarantee obligations by Abu Dhabi’s Mubadalla. The announcment included these statements:

“Signum Guaranteed Obligations means the notes and loans of Signum Magnolia Limited which are collateralised by the USD 1.75 Billion 5.75% Guaranteed Notes due 2022 of 1MDB Energy (Langat) Limited guaranteed by 1MDB and further guaranteed by IPIC.”

There does not appear to be any mention of Signum Magnolia Limited in any previous IPIC announcement which concerned 1MDB. Signum is a Cayman Island incorporated company. However Emirates NBD Bank describes in its 2012 Annual Report as a Malaysian company saying:

“Some of the notable transactions concluded during the year included acting as mandated lead arranger, advisor and bookrunner for syndicated loans valuing USD 6.5 billion, arranged for high profile clients like Signum Magnolia Limited-Malaysia” [Realpolitkasia]

Sahathevan appears to have identified a clear and till now hidden off-shore element to the raising of the 1MDB Goldman bonds, acknowledged for the first time by one of the public bodies involved.

After all, US$6.5 billion identically matches the total sum raised by Goldman for 1MDB over the three bond issues during the period 2012-2013 and Sarawak Report has reported that ‘Magnolia’ was the password for the first offering document for 1MDB Energy (Langat) which was secretively restricted only to Goldman’s private clients – the flotation was coded ‘Project Magnolia’.

That a Malaysian owned limited company incorporated in the Caymans named Signum Magnolia has been stated by NBD bank as having raised $6.5 billion during that period is clearly a coincidence too far. Yet, so far, it’s all smoke and mirrors for anyone attempting to understand the fate of this public money.

Goldman Sachs ought to explain why it adopted such a convoluted off-shore instrument to rais public money for the Malaysian Government and why was it charging so much? There are those who argue the benefits of the off-shore system, but surely it has no place in public finances as the thefts that ensued over 1MDB amply demonstrate?

The Mysterious Roger Ng

The Goldman Sachs’s 1MDB bonds represented merely the latest development in these sorts of activities. Leissner’s key associate in a number of deals involving close ties with Malaysian decision makers was a local banker named Roger Ng, whose involvement in the over-priced bonds was flagged up by Reuters as early as 2014.

Leissner had poached Ng from Deutsche Bank, where he appears to have forged close relations with the Sarawak Chief Minister, Taib Mahmud as well as other well placed decision makers in Malaysia.

Sarawak Report and other anti-corruption campaigners, including the Swiss Bruno Manser Fund, have raised concerns over the close association of Deutsche Bank and the Taib family, particularly through the jointly controlled investment fund, Kenanga Holdings.

Whistleblower Ross Boyert had further revealed that Deutsche Bank also acts as nominee for a Taib family off-shore company in Guernsey, effectively disguising the family’s ownership of Sogo Holdings, which owns several North American properties and is believed to be linked to shares in Asia’s Sogo department stores.

Arriving from Deutsche Bank at Goldman Sachs in 2005, Ng was rapidly involved in raising huge sums of public money via off-shore bonds to ostensibly finance Taib’s Sarawak government and its so-called SCORE industrialisation scheme, providing something of a template for the later 1MDB bonds.

In 2011, for example, Goldman Sachs raised $1.5 billion dollars on behalf of the Sarawak Government via Labuan through a private entity named Equisar International Incorporated. A report by the NGO Global Witness highlighted the irregularity of handling public loans “under the radar” in this fashion and pointed out the glaring corruption of Sarawak’s government and the handling of its public finances.

As Sarawak Report had earlier pointed out, Taib’s use of a so-called Approved Agencies Trust Fund to repay these bonds (amongst other unspecified debts) represented an unaudited ‘Black Hole’ comprising almost half the state budget, an issue that had been identified by the DAP local opposition leader YB Chong.

In June 2103 Sarawak Report exposed another huge secretive off-shore bond issue linked to SCORE, this time on behalf of Sarawak Energy (SEB), a public body which had failed to produce annual reports since 2010. The cash was supposedly to fund its mega-dam building ambitions, which have benefitted numerous Taib family companies and monopolies.

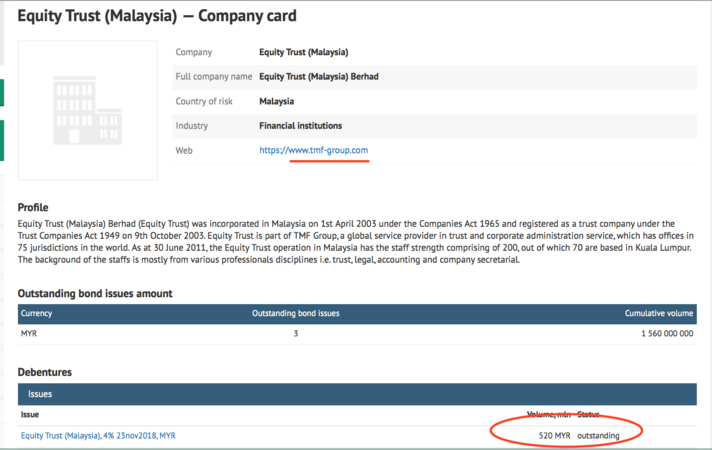

A lending facility of no less than $15 billion ringgit had been raised in June 2011, again through Labuan, however not through a mainstream bank on this occasion, but rather through a subsidiary of the wealth management company TMF called Equity Trust (Malaysia). The Equity Trust branch in the British Virgin Islands whose (Equity Trust BVI) coincidentally also manages the off-shore subsidiary of the Taib family’s enormous conglomerate CMS.

At least RM520 million has been recorded as having been raised on the local markets relating to the facility so far.

Once again, critics like DAPS Chong Chieng Jen argued that the rates of interest were ludicrously high (6% instead of 2-3%). The local opposition leader was thrown out of the state assembly for his pains, on the order of Taib’s appointed Speaker, having aptly described Sarawak’s off-shore bonds as “David Copperfield economics” :

“Adenan [successor chief minister] has tried to justify these borrowings but failed miserably,” said Chong. “It only confirms my suspicion that there are great improprieties in these offshore loans taken by the Sarawak Government.”

..Who are the bond holders?” he asked. “Are these bond holders related to the top Barisan Nasional (BN) leaders with a lot of money overseas? Why is the Sarawak Government paying so much interest on these loans?” [Chong Chieng Jen, FMT ]

The Goldman bond was to raise the further US$1.6 billion through Equisar in the following month of July. Global Witness has identified US$2.7 billion in bonds raised by Sarawak through Labuan as of 2014, whilst the remaining enormous tranche of the RM15 billion secured by TMF appears pending.

Roger Ng and Leissner moved smoothly on the following year to raise the series of loans for 1MDB, having been engaged by its predecessor the Terengganu Investment Authority to help set up the original fund to raise investment on its oil revenues.

Banks In The Cross Hairs

So, it is time for the role of international banks to move centre stage over 1MDB. After questions started to be raised about the cost of Goldman’s services to 1MDB amid evidence of gross spending by Jho Low and Riza Azia, Roger Ng quietly departed from the bank at the start of 2014. However, he maintained a close friendship and business ties with Tim Leissner, by now the bank’s South East Asia boss who had built so many deals on his connections.

Leissner invested in a major soft drinks company Celsius, where Ng was appointed Asian Managing Director, before departing as late as August this year. 1MDB investigators are believed to also be looking at the transfer of $17.5 million by Leissner’s ex wife to Ng’s wife shortly after the 2012 bond deals.

What is clear is that Ng (who is back in Malaysia and unlikely to be in a position to leave) is now a top target for US investigators probing the role of Goldman Sachs and there has been talk of his imminent arrest since June as Malaysian authorities draft charges.

In short, dodgy loans that raise billions on the taxpayer through off-shore instruments with zero accountability are not the sort of thing that licensed global financial institutions, whether banks or wealth managers for the kleptocrats in charge, ought to be in the business of. Particularly when the purpose turns out to be the obvious one, as in 1MDB, which was massive theft.

There will be massive lobbying by these banks to persuade the DOJ and others to drop these investigations, but with US$600 million of Malaysia’s money at stake (the fees Goldman Sachs charged) the truth must come out – and along with it a great deal more understanding of how major banks have interacted with ‘Treasure Islands’ to serve their most wealthy (and criminal) customers.