Entering 2017 makes almost two whole years that the 1MDB saga has been in the process of unravelling. It is now established as the biggest global kleptocracy case ever and yet the protagonists are still fighting furiously to maintain their innocence (in the face of a deluge of evidence) and to hang onto power in Malaysia.

Sarawak Report has burrowed into the story and pieced together the puzzle over the months, supported by many avid followers of the unfolding saga. It has often felt like a mini-series in action for us ‘aficionados’.

Now (maybe) we are into the Final Act, as Prime Minister Najib Razak sets about his attempt to pull off an ‘election win’, which he would clearly treat as permission to carry on robbing the country. Yet, as confidence begins to fail within and outside of Malaysia, so his chances are starting to ebb. It promises to be a knuckle-biting drama till the end.

But, maybe you got onto the story a little bit later than some of us or maybe you didn’t follow every twist and turn?

To help those who may be feeling just a little bit lost on the detail of this scandal, Sarawak Report offers this hopefully helpful summary of the story so far – and the good news is that, whilst the detail of the money-laundering of billions of dollars may have created a headache for investigators, the scam itself was surprisingly simple.

Suspicious from the start

1MDB (One Malaysia Development Berhad) was set up by Najib as his flagship development programme, straight after he took over from Badawi as Prime Minister in 2009. It was themed after his favourite early slogans of reform and unity, which now sound like lost ideals for a man, who is ruling through civil rights crackdowns and promoting aggressive bigotry towards minorities.

From the start, many were suspicious about the real purpose of this ‘sovereign investment fund’, which went about immediately raising huge sums of money, with little apparent thought given to what programmes it would be spent on or why. Many believed Najib was really more focused on winning the up-coming election, given the recently released Anwar Ibrahim had presented the first serious opposition challenge to the dominant BN coalition during the so-called ‘election tusnami’ of 2008 and now was leading a momentum for change.

So, insiders immediately suspected that 1MDB’s primary purpose was not really development but to act as Najib’s secret slush fund.

This Prime Minister cum Finance Minister already held a reputation for having been a very corrupted Minister of Defence for many years (the French courts are still processing his Scorpene Submarine deal, which French prosecutors say involved vast bribes to Najib) and he also has a notoriously extravagant and forceful wife to keep happy.

So when the then Terengganu Investment Authority (1MDB’s original name) started raising a billion dollars at an unnecessarily high rate of interest, eyebrows were quickly raised.

Opposition figures also noted that the flamboyant youthful Chinese Malaysian, Jho Low, who was close to Najib’s wife Rosmah, appeared to have a strange role as an advisor on the formation of the fund and the structuring of its investments. Why did Najib need this ‘fixer’ in his 20s to manage this new fund?

By September the entire first billion raised had been hastily sent abroad and plunged into a single ‘joint venture’ with a previously unheard of foreign company named PetroSaudi, which it was evetually learnt was run by a group of young Saudis, who had contacts with Jho Low.

Official statements at the time gave no mention of what the venture was about or what exactly it would be investing in. Instead, these communiques focused on the claims that PetroSaudi was a Saudi state connected company and that Saudi Arabia was injecting money into the first of a series of expected investments in Malaysia through this ‘government to governement’ vehicle.

The Prime Minister had said in a press release that Malaysia’s 1MDB was investing its $1 billion in cash and PetroSaudi was investing $1.5 billion. Much was made of the fact that the part-owner of PetroSaudi was Prince Turki bin Abdullah, a son of the then King of Saudi Arabia. This was the beginning of lucrative Middle Eastern investment in Malaysia, thanks to the progressive, modern new Prime Minister, so the narrative ran in the Malaysian media.

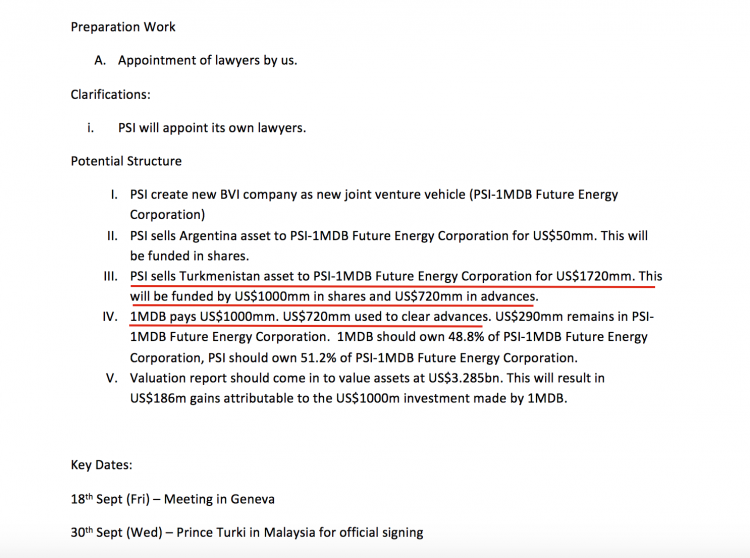

PetroSaudi held no official status in Saudi and neither had it actually injected a penny into the deal, but had supposedly made its $1.5 billion contribution (resulting in a commanding 60% of the shareholding) in alleged ‘assets’ – these assets were based on a fake valuation of the company organised by PetroSaudi itself, which included an alleged oil field concession in Turkmenistan, supposedly worth $2.9 billion.

“The Plan”

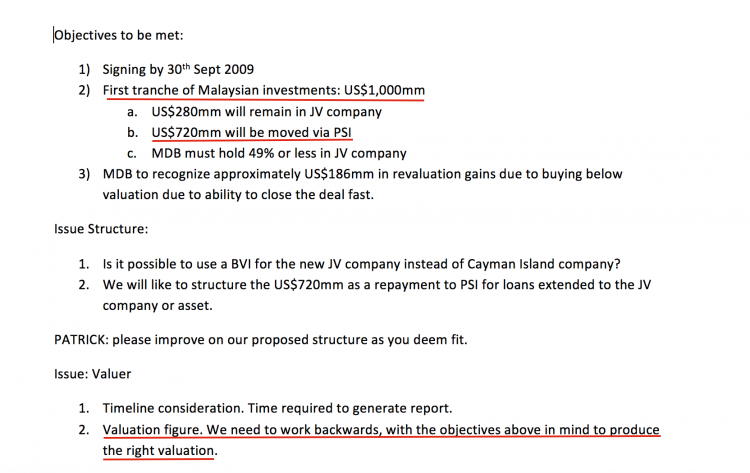

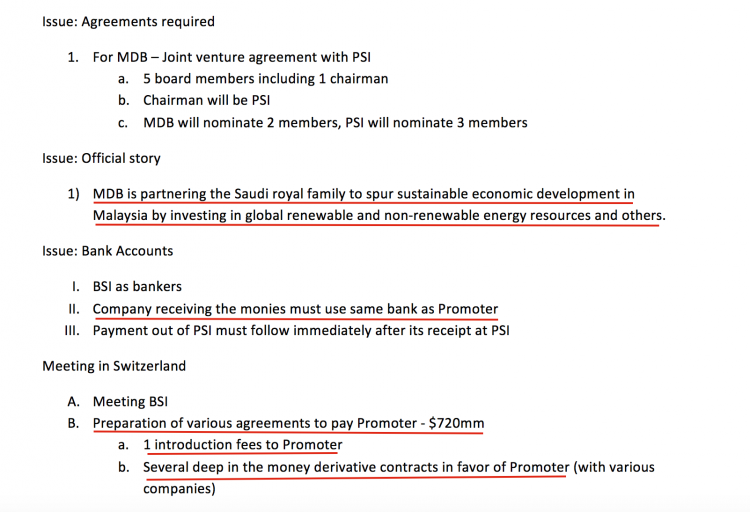

Jho Low and PetroSaudi’s Directors had colluded from the start to frame these deceptions as early correspondence shows. One document named ‘The Plan’ framed by Li Lin Seet, Jho Low’s assistant, explains how the collaborators planned to organise for the bulk of the money (orginally $720 million, later to be reduced to $700 million) to be diverted to ‘The Promotor’ i.e. Jho Low, using PetroSaudi as a front.

PetroSaudi needed to work back from a valuation of at least $3 billion to justify that payment (supposedly in return for the assets injected into the venture). In fact PetroSaudi was little more than a shell company.

THE PLAN

As PetroSaudi’s own database, revealed by the whistleblower Xavier Justo would later prove, PetroSaudi did not in fact own the oil field in Turkmenistan, on which the valuation was made.

When the 1MDB Board found out about the outrageous deal, which had been pushed through by Najib and Jho Low in just three weeks, its Chairman resigned.

However, as far as public information was concerned there was silence over this deal for nearly a year, provoking considerable criticism from opposition figures like Anwar Ibrahim and later DAP’s Tony Pua and Dr Mahathir within Najib’s own UMNO party.

In 2010 PetroSaudi suddenly came back onto the Malaysian scene with a surprise offer to buy over the UBG group, which belonged to the Chief Minister of Sarawak who had been trying to sell for some time. Najib needed Sarawak seats to have a hope of winning any election.

PetroSaudi offered top dollar for the company and another person to benefit from the windfall was none other than Jho Low, who had himself bought up the totality of a massive new share issue by the company just a year earlier. Again eyebrows were raised in Malaysia as insiders started to put two and two together.

Ostentatious behaviour caused further suspicion

In the meantime, the twenty something Jho Low had in the course of late 2009-2010 started to attract considerable global publicity for his growing ostentation and high-spending. Given he himself at that time said his parents were not particularly rich, the stories of Jho’s antics in Las Vegas, St Tropez and the rest of the world’s hotspots was bewildering to Malaysians.

Jho at first explained that he was just a fantastic deal breaker and that the lavish parties were just something he arranged for his rich clients (implying it was them not he who paid). Later he changed his story and explained his family was rich after all and called himself a third generation billionaire…

Financial difficulties

Meanwhile, 1MDB’s accounts… or rather the late delivery of them and thair lack of detail, started to stack up more comments and complaints. By 2013 the fund was on to its third set of auditors with almost a year’s delay in the report for that year, after KPMG were removed (because they refused to sign off on the PetroSaudi deal it later emerged) and were replaced by Deloittes.

Nevertheless, BN/UMNO in May of 2013 did convincingly win what was generally agreed to be a particularly dirtly election, flooded with huge amounts of cash openly handed out to voters across East and West Malaysia.

In Jho Low’s home state of Penang the young businessman personally took command of a hugely expensive attempt to win back the opposition stronghold – an attempt that failed.

By the end of 2013 1MDB was servicing approaching $12 billion in debts.

Later 1MDB deals

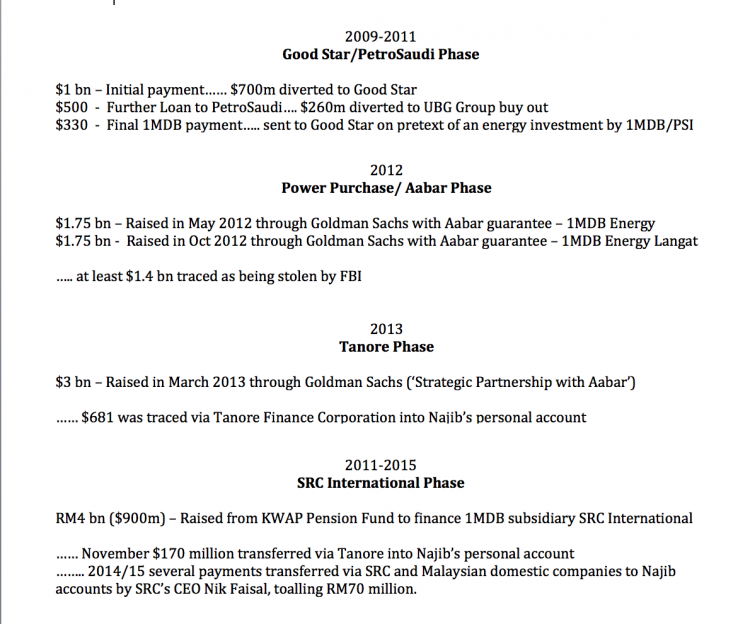

Those debts were the result of further borrowing. Following the PetroSaudi deal and in advance of that 2013 election win, 1MDB had embarked on three further similar ‘state to state’ joint deals, which were likewise flagged up as exciting Middle Eastern investment in Malaysia, even though 1MDB had in fact again raised the money itself (once again with remarkably high rates of interest and fees entailed).

These later deals involved Abu Dhabi’s Aabar sovereign wealth fund, which was a subsidiary of the major IPIC fund run by Sheikh Mansour. The prominent Emirati official Khadem Al Qubaisi, who was both the CEO of IPIC and Chairman of Aabar, was a contact of Jho Low’s.

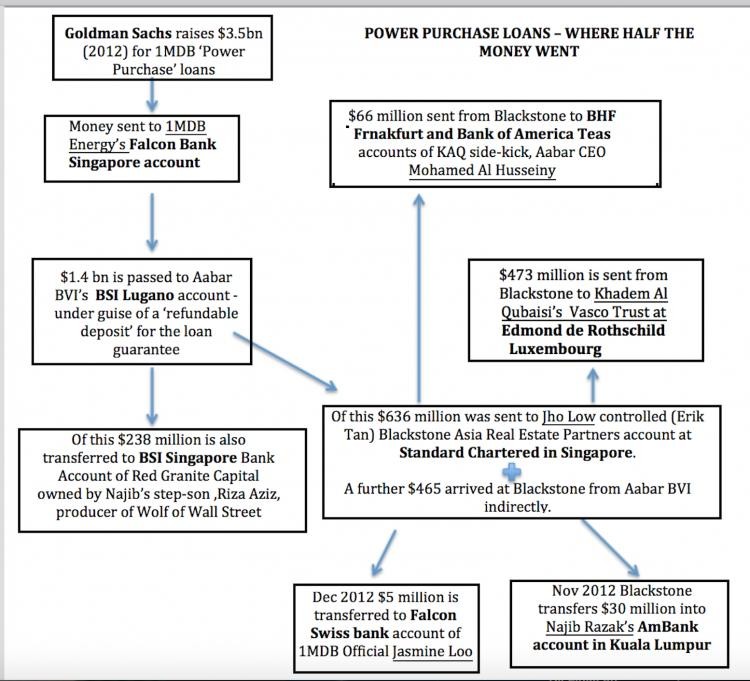

In this arrangement three separate bond issues were backed by a guarantee from the Aabar. Goldman Sachs’s South East Asia boss, Tim Leissner (another contact of Jho Low and Najib’s) who raised the bonds, had apparently advised 1MDB to undertake the joint guarantee structure, because 1MDB itself had no equity on which to base the borrowing.

The three deals, totalling $3.5 billion, involved two so-called ‘Power Purchase’ loans for $1.75 billion each, raised in May and October 2012, and then a third $3 billion loan raised very hastily in March 2013 (just before Najib called the election). The third loan was supposedly Malaysia’s contribution towards a joint strategic partnership with Abu Dhabi to develop a new business district in KL (the still undeveloped Tun Razak Exchange).

Abu Dhabi itself never put up any money for any of these arrangements. Yet, as with the PetroSaudi deal, they were publicised in Malaysia as state to state joint ventures bringing Middle Eastern investment into KL – a sign of confidence in the masterful management (and moderate Muslim influence) of Prime Minister Najib.

SRC

There was one further ‘major venture’ involving 1MDB, which involved the borrowing of RM4 billion (c $1 billion) in 2011 from the local civil service pension fund, KWAP. This money was injected into a new subsidiary set up under 1MDB, SRC International, which was controlled by a CEO named Nik Faisal Arif Kamil. Also a close associate of Jho Low, Nik Kamil had moved over from UBG Bank to 1MDB at the time of its buy by PetroSaudi (although many suspected from the start that the money had actually come from 1MDB, where Nik was appointed Chief Investment Officer).

Significantly, Nik Kamil was also designated as an ‘authorised person’ managing a series of accounts held in the name of Najib himself at AmBank. Large sums of money were to start arriving in these domestic accounts after 2011 (signed in by Nik) – much of which was eventually to be traced back to SRC International, where the payments had been also signed out by its CEO, Nik Kamil.

Money Problems

By late 2013, after all these sums had been raised and ‘investments’ made, it became plain that 1MDB’s debts were beginning to stack up. Some money had been used to buy some power plants in Malaysia, at what were generally agreed to be heavily inflated prices from BN cronies (namely Ananda Krishnan and Genting), however critics said that the fund appeared to have little to show for its money.

By 2014, 1MDB was approaching $12 billion in debt and the Minister of Finance (also Najib), who was the Chairman of the Advisory Board of 1MDB (it would later be discovered that he was also secretly the sole shareholder and sole signatory and authorised decision-maker for the fund) started to talk about a public floatation to inject finances back into the situation.

Many worried those finances would come from gullible investors or Government-linked companies, over which the Prime Minister had far too much personal influence.

Unravelling the truth about 1MDB

Sarawak Report first started probing this situation at the start of 2014, just as 1MDB’s finances had started to become critical. January of that year saw the launch of the $100 million blockbuster Wolf of Wall Street, which we learnt was produced and financed by a rookie film company owned by none other than Rosmah Mansor’s youthful son Riza Aziz.

Enquiries soon revealed that Najib’s step-son, who had spent just two years as a junior associate banker in London, had also come into ownership of a mansion in Beverley Hills and a penthouse in New York. His prominent companion, according to reporting in Hollywood, was none other than Jho Low, who was credited at the end of the movie.

Receiving the Golden Globe Award, lead actor Leo DiCaprio thanked “Jho and Riza for taking a risk on the movie”.

Red Granite took legal action after Sarawak Report published the information and enquired who was funding the film. We asked if it was Jho Low and whether Low’s involvement with 1MDB was connected? However, Riza did not pursue the action and later announced that his funder was in fact the CEO of Aabar, Khadem Al Qubaisi’s side-kick, Mohamed Al Husseiney.

Sarawak Report pointed out that this also represented an apparent conflict of interest, since Aabar was also closely connected to 1MDB.

Meanwhile, we discovered from London court documents that 1MDB had been backing joint business ventures by Jho Low and Aabar, who tried to buy out London’s most expensive Claridge’s Hotel chain. 1MDB had provided money for the bid on the grounds that the Aabar/ Jho Low venture was to establish a top Hotel Management School in KL, which wasn’t true.

Xavier Justo

In June 2014 Sarawak Report learned through enquiries of a possible whistleblower. This was the former PetroSaudi Director Xavier Justo, who had obtained documents relating to his former company after leaving following a dispute. Through these documents he had been shocked to discover that the bulk of the c. two billion dollars invested in the ‘Joint venture’ had been stolen and was now threatening to expose his ex-colleagues.

After several months of discussions with Justo, Sarawak Report introduced him to The Edge media group, who said they were willing to purchase the documents. For Justo the promised sum of $2 million (which has not in fact been paid) represented money still owed to him by PetroSaudi of which he had been a founding director.

In return for organising the agreement Sarawak Report also obtained a copy of the documents. From these documents it became plain that of the original $1 billion invested in the PetroSaudi Joint Venture of September 2009 $700 million had been immediately siphoned off into an off-shore company owned by Jho Low, called Good Star Limited, registered in the Seychelles.

Good Star then immediately paid Tarek Obaid $85 million, $33 million of which was passed to another PetroSaudi Director, Patrick Mahony. The rest of the money was paid to PetroSaudi to invest in an off-shore drilling contract in Venezuela. The PetroSaudi data further demonstrated that the following year in 2010 more money had been funnelled from 1MDB to PetroSaudi, which was then used to buy out Jho Low and Taib’s investment in UBG Group – as had long been suspected.

Altogether, the Justo data showed that of $1.83 billion paid into PetroSaudi around $1.5 billion was stolen by Jho Low and the rest went to PetroSaudi to start its operations – before it had merely been a shell company. Sarawak Report together with the Sunday Times and The Edge ran several stories based on this data, which was also handed to the authorities in several countries, beginning a major global investigation into the thefts from 1MDB.

The other dodgy deals

Meanwhile, Sarawak Report was separately gaining information about 1MDB’s later dodgy Abu Dhabi deals. Sources responded to reports on this blog to say they had evidence about Khadem Al Qubaisi’s (KAQ) extravagant purchases of properties and also the Hakkasan nightclub chain in the US. We also learnt he had received half a billion dollars through a series of kickbacks into his Luxembourg bank account at Edmond de Rothschild bank.

These kickbacks were plainly based on the Power Purchase deals of 2012 and came from 1MDB according to our information. There were further business deals linking Jho Low and Khadem Al Qubaisi’s private companies in 2013, for example the Coastal Energy buy out for $2.3 billion by the two businessmen, backed by Aabar.

Aabar/IPIC almost immediately responded to our reporting by sacking KAQ and also his collaborator Mohamed Al Husseiny, both are currently jailed and charged with corruption in Abu Dhabi. The Edge further pointed out that although 1MDB’s accounts reported that payments totalling $3.5 billion had been made to Aabar, supposedly as deposits for its guarantees on the loans, IPIC had made no public record of receiving the payments.

Later, investigations by regulators were to establish that the money had actually gone to a bogus off-shore subsidiary also named Aabar (Aabar Investments PJS Limited) in BVI, which had been set up separately by KAQ and Husseiny. Money passing through this entitiy was used to make payments to Najib, KAQ and Husseiny – a direct theft from 1MDB by these three men.

$681 million paid to Najib!

These revelations by Sarawak Report both into the PetroSaudi and Aabar deals took place just at the time that 1MDB was facing financial meltdown and sparked a political crisis in Malaysia in early 2015. The planned IPO was called off and Najib Razak, while denying any impropriety, was forced to set up investigations into the management of the fund.

The Auditor General, Parliamentary Public Accounts Committee and four official Task Forces (under the police, Attorney General, Central Bank and Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission) were deputed to investigate the whole affair.

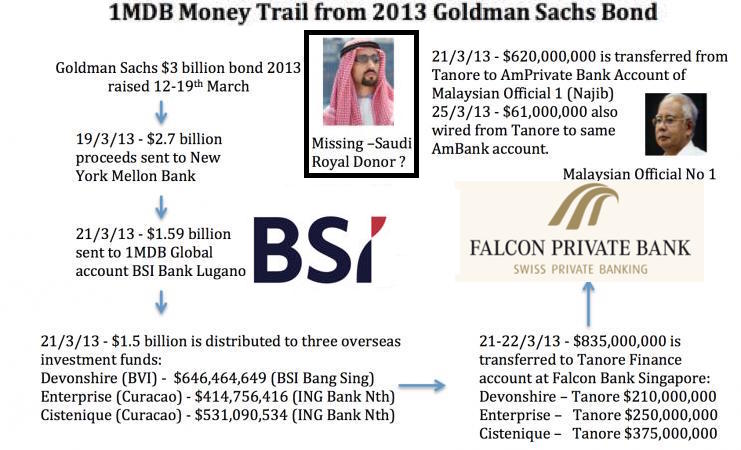

Sarawak Report obtained a series of leaks from various separate sources relating to these multiple investigations. The most dramatic of these it shared with the Wall Street Journal. This information showed that investigators had established that a huge payment of $681 million had been paid into Najib Razak’s own personal KL account at AmBank between March 21-23rd 2013, just before he called the General Election.

Sarawak Report noted that this payment followed the final $3 billion bond issue by Goldman Sachs (the Strategic Partnership for developing the KL business district) just a few days earlier on March 19th. Sure enough, when the US Dept of Justice published its findings in July last year, investigators confirmed that the money had travelled in a matter of just two days from Goldman Sachs, to 1MDB and then on to Najib’s account via three bogus funds and Falcon Bank (owned by Aabar). BSI Bank played a key role also in the money laundering of these stolen funds.

The evidence showed that the money entering Najib’s account on the eve of the 2013 election was not therefore the money stolen from PetroSaudi via Good Star back in 2009, but came from the later source.

The DOJ/FBI investigation did however trace how the earlier PetroSaudi cash, as well as the later Aabar related Power Purchase deals of 2012, had been spent on a variety of luxuries and business ventures, including hotels, properties and expensive artwork for Jho Low and Riza Aziz – and also funded the film Wolf of Wall Street.

Sarawak Report had already learnt that several earlier payments had also been made into Najib’s AmBank account, which before the election had inflated the account to over a billion US dollars.

After the election, Sarawak Report reported, this account was closed down and the money was returned back to the Singapore account of Tanore Finance Corporation. Tanore was owned by yet another Jho Low associate named Eric Tan and after the money came back it was laundered in a variety of ways through the US, particularly through the purchase of expensive paintings.

Meanwhile, Sarawak Report separately detailed the extravagant and lavish expenditures and life-styles of the key players in these deals, Jho Low, KAQ and their various hangers on like Eric Tan.

Kevin Morais and the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission

During the 2015 task force investigations the MACC uncovered further devastating details, showing large sums had passed from the SRC International account (using the borrowed money from KWAP) to Najib’s other KL accounts, managed by Nik Kamil.

Based on the information relating to these purely domestic transactions the joint task forces linked to the MACC and Attorney General’s Office, together with the Bank Negara and Inspector General of Police agreed that the Prime Minister must be charged. They gained the consent of the Agong.

However, the Prime Minister gained warning of the development and instead used armed officers to way lay the Attorney General at his office and unconstitutionally forced him to resign. He then appointed a loyalist to replace him and sacked his Deputy Prime Minister as well as other Ministers who had criticised him over 1MDB – closed down the task forces and removed key members of the Public Accounts Committe, by appointing them as ministers. Crucial to the coup was the decision of the Inspector General of Police to support the Prime Minister instead of the independed official bodies, which had concluded he must be charged.

Sarawak Report was notified the following day about what had happened by the public prosecutor Kevin Morais, who had been pivotal to the AG/ MACC investigation and the drawing up of the draft charge sheets against Najib. Morais sent Sarawak Report a copy of the arrest warrant, which we published. Kevin also passed information on the findings by the MACC, including credit card expenses by Najib, to Sarawak Report.

A few weeks later Morais, who had been planning to come to London, was abducted from his car in traffic in KL. He was found ten days later tortured and murdered, his body encased in a drum of cement. Gangsters have been blamed.

Final tally over $7 billion

Whilst Najib has carried on to implement major crack downs in Malaysia, effectively criminalising all criticism of himself and 1MDB, numerous investigations have opened into the huge sums of missing money from the PetroSaudi, Aabar and SRC related deals in several countries.

Much of the money had been transferred through Switzerland or Swiss banks and Zurich launched investigations along with Singapore, which has prosecuted officials from BSI Bank, which handled much of the money and concealed the fact that large sums had been lost. Falcon Bank, which belongs to Aabar and which housed the Tanore account is likewise under criminal investigation.

Above all, the United States has undertaken a major investigation based on the fact the money laundering was carried out through dollar transactions mostly in the United States. In July the joint DOJ/FBI civil asset seizure document laid out in detail the money trail for much of the stolen money. It named Jho Low as the prime operator, as well as Riza Aziz, who did indeed receive the finance for the Wolf of Wall Street straight from 1MDB money stolen from the power purchase deals.

The DOJ/FBI court filing also points a finger directly at Najib, referred to as Malaysian Official One. It makes clear Najib was a key orchestrator of the theft from 1MDB and also the biggest beneficiary of the stolen money. When the eventual criminal prosecutions follow the civil sequestration case, it seems therefore inevitable that Najib will be named as the prime criminal in the case.

Nevertheless, Najib and his fellow ministers remain in denial. Last January the new Attorney General declared the Prime Minister “cleared”, even though the MACC and Bank Negara protested the failure to prosecute on the evidence. Documents, which Attorney Generl Apandi himself waved in front of the press conference, clearly showed how further money had been traced from SRC to Najib’s accounts (totalling at least RM70 million).

Malaysian Auditor General’s Report

When the Auditor General finally produced his own report into 1MDB in May Najib declared it an official secret, although Sarawak Report later gained a copy and published it online.

That report shows that the AG has calculated that over $7 billion has gone missing and unaccounted from the fund. This particularly includes the alleged ‘profit’ from the PetroSaudi joint venture, which 1MDB and the company claim was settled in 2012.

According to PetroSaudi, it paid back all the money with a profit totalling $2.3 billion, thereby settling its ‘borrowing’ from 1MDB. However, instead of using this supposed hard currency to pay its pressing debts, the Malaysian fund announced it had decided to invest it with a dubious unlicenced fund in the Cayman Islands, reporting to Deloittes that it had purchased ‘units’ to the value of the money.

1MDB subsequently told Deloittes this money had been “redeemed” from the Cayman fund and used to pay for ‘options’ to Aabar and also running costs and debts, with the remaining billion being invested in BSI Singapore. Documents submitted to the AG investigation indicate that in fact money was recycled on a round tripping exercise to fool the auditors that it had been sent from entities related to the Cayman fund.

Sarawak Report learnt last year from the Singapore investigations that there was in fact no cash in the BSI account. This caused Deutche Bank to withdraw a billion dollar loan in March 2015, which was what 1MDB had in fact been using to pay out its debts.

That in turn forced 1MDB to fall back upon its guarantee with Aabar, which the Mohammed Al Husseiny agreed to fund shortly before being sacked. Apparently, IPIC itself was unaware of the commitment entered into by its top officials and the Goldman boss Tim Leissman has also been sacked for his inappropriate role in a series of deals for which his bank had charged $600 million and which had gained him huge bonuses and plaudits originally from his bosses.

After the DOJ filed its complaint in July, Deloittes promptly resigned as 1MDB’s auditors and confirmed they can no longer stand by the accounts they filed.

Final Act opens with 2017 and looming election battle?

Najib has continued to use his billions to pay local supporters, as leaked evidence from his bank accounts shows.

Numerous cheques have been drawn from his slush funds to individuals from his party – the office holders whose votes support his continuing position in power. In return, these individuals have chosen to believe Najib’s excuses for his money, including his explanation that it came from a small time royal from Saudi Arabia, (one AbdulAziz al Saud, who has connections with PetroSaudi). Najib says it was AbdulAziz who passed him the $681 million dollars as a “donation”, plus the many other earlier payments into his account – including a further $170 million paid in November 2011 from SRC. He also claims that he returned most of the money via Tanore, although the DOJ say the money was traced to laundering in the states.

Malaysia’s ruling elite is therefore entering 2017 entrenched in this corrupt collaboration with a leader, who has stolen the money they are enjoying from the public purse.

As the economy groans and foreign investor confidence evaporates, this group are clearly further planning to squeeze one last dollop from Malaysia’s public funds. Yet another $680 million is the payment being offered by FELDA to buy out Eagle Plantations from Najib’s close friend the Indonesian businessman Peter Sondakh in a blatant further deal to pad out UMNO’s pre-election purse at the expense of Malaysia’s poorest farmers.

The logic is that if Najib can manage to again buy the next election he will at last be able to put behind him the scandal that after two years has refused to go away, ignore the foreign critics and be safe from justice at last.

Will he succeed?

The answer will come in 2017…. probably